“They do not know a country that has successfully implemented multilingualism.”

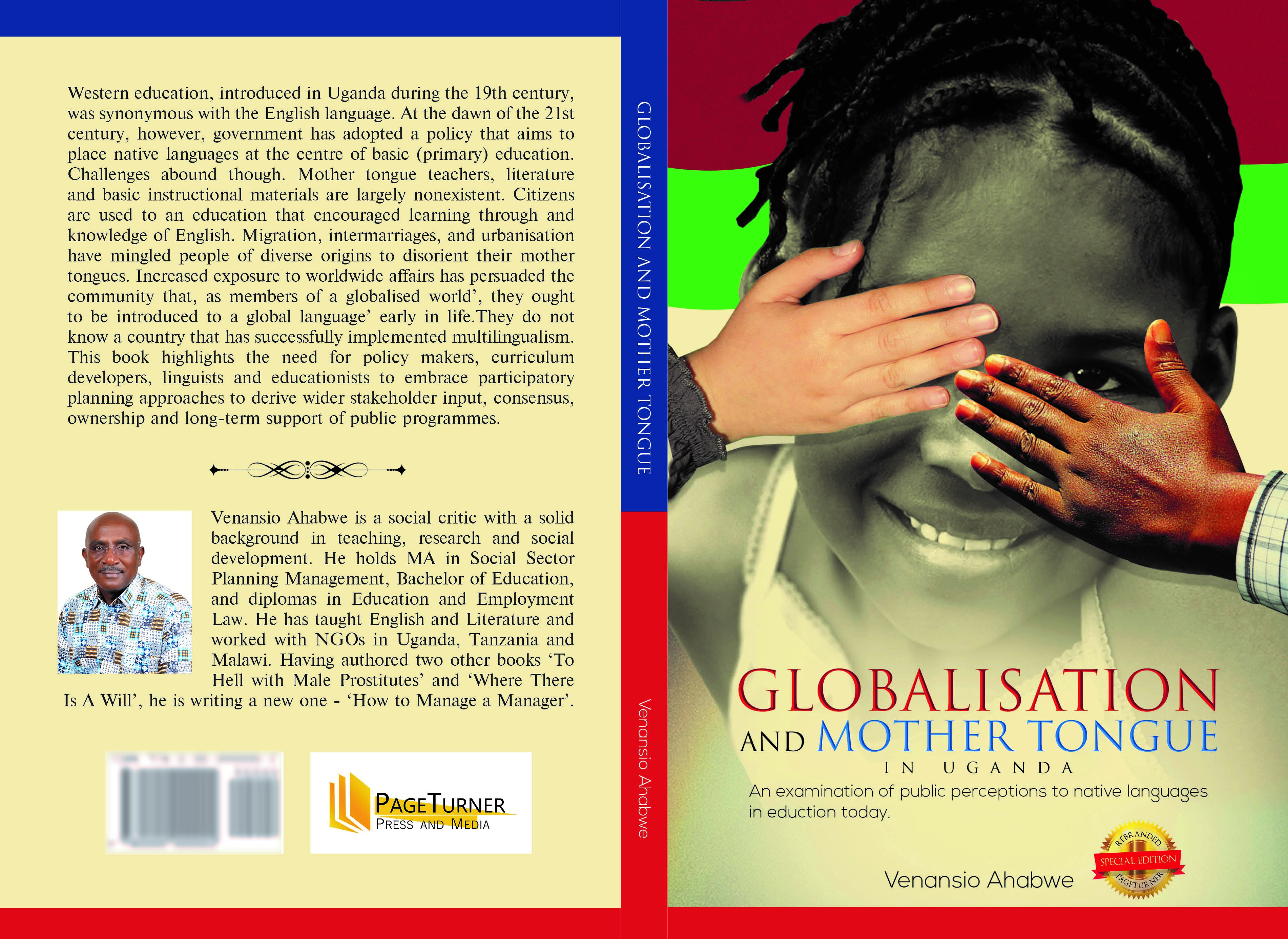

Western education, introduced in Uganda during the 19th century, was synonymous with the English language. At the dawn of the 21st century, however, government has adopted a policy that aims to place native languages at the centre of basic (primary) education. Challenges abound though. Mother tongue teachers, literature and basic instructional materials are largely nonexistent. Citizens are used to an education that encouraged learning through and knowledge of English. Migration, intermarriages, and urbanisation have mingled people of diverse origins to disorient their mother tongues. Increased exposure to worldwide affairs has persuaded the community that, as members of a globalised world', they ought to be introduced to a global language' early in life. They do not know a country that has successfully implemented multilingualism. This book highlights the need for policy makers, curriculum developers, linguists and educationists to embrace participatory planning approaches to derive wider stakeholder input, consensus, ownership and long-term support of public programmes.

|

Author ID: PT0000354 Book ID: B00001152 Page Count: 136 Listings 2. Amazon Listing (Ebook)

|

|---|

REVIEWS

![]()

Uganda’s mother tongue teaching policy largely misunderstood.

Background: In 2007, Uganda’s Ministry of Education and Sports rolled out the Thematic Curriculum that introduced mother tongues as the media of instruction in lower primary school grades (P.1–3). The curriculum is still in force, within the ambits of the Mother Tongue Teaching Policy, which stipulates that schools, save for some in urban areas, should teach all subjects, except English, through the mother tongue. Every school adopts the dominant language of the community in which it is situated as a language of instruction or retains English only if the dominant community language is unclear.

Description of the intervention: As the new policy commenced, it met considerable hostility from many stakeholders. Teachers, civil society groups, and some individuals strongly criticised it. In a space of ten months, this writer compiled about 30 media articles which majorly despised the mother tongue teaching initiative. This writer therefore undertook a study both to understand public perceptions about the policy and also as education policy analysis to satisfy requirements for the award of master’s degree from Makerere University. The study was conducted in Jinja Municipality, an urban area that should ordinarily be exempted from the mother tongue teaching policy.

Lessons: Findings from the study were rather odd. Majority (60%) of the schools believed that they were indeed exempted from teaching local languages and thus maintained English as a medium of instruction. Yet, the remaining 40% thought that all schools, regardless of their settings, were obliged to embrace local languages. Without proficient teachers, schools adopted mother tongues and were largely at pains to conduct successful lessons. In one school, pupils spoke Lusoga as their mother tongue, but their teachers spoke Luganda, hence, the school adopted the teachers’ language with a strange justification.

The most popular beliefs among respondents was that the Thematic Curriculum was intended primarily to preserve traditional culture, and this was the strongest value about it. Others said that the new language policy was formulated by people who went to school during colonial or immediate postcolonial Uganda and studied in mother tongues. Some participants also said that the policy was introduced to ‘decriminalise’ the use of local vernacular in schools and others perceived mischief as the policy would make learners and teachers stuck in particular locations, and this would also alienate rural schools from quality education and make them less competitive in national examinations.

Implications: The researcher understood that that an educational policy ought to absorb viewpoints of diverse stakeholders for it to be relevant, widely supported, and ultimately successful. From the outset, the mother tongue teaching policy was grossly misunderstood by most key stakeholders. Participants considered it more a liability than an asset in children’s learning processes. Clearly, the policy was hastily introduced: there was no systematic preparation in terms of consultations, instructional materials development, and orientation of teachers.

About the writer: Venansio Ahabwe is the author of a book: ‘Globalisation and the Mother Tongue in Uganda. He is a Social Scientist; Teacher of English Language and Literature; Technical Advisor for Social and Behaviour Change; and works at Johns Hopkins University Centre for Communication Programs Uganda.